The Birth Of Worship

Man, so long as he remains free, has no more constant and agonising anxiety than find as quickly as possible someone to worship.

- Fyodor Dostoevsky

Self-actualisation is an unfolding toward a higher state. We are hardwired to explore and learn about our surroundings as well as look for our place in society. How we actualise depends on our personality, our environment, our DNA, our influences, and what resonates with our True Self.

We pursue actualisation in countless ways, such as public service, research, literature, art, sports, philosophy, study, business or raising a family. Once something resonates with us, we immerse ourselves in it. This begins a process of deepening our relationship with the world, deepening our maturity, and most importantly, deepening our connection with our True Self. In doing so, we move into our spiritual centre and direct it toward a higher purpose, hence emulating all other life forms. From the single-celled organism to the mighty blue whale, life has a great deal to teach us, not only about physical growth, but also our actualisation.

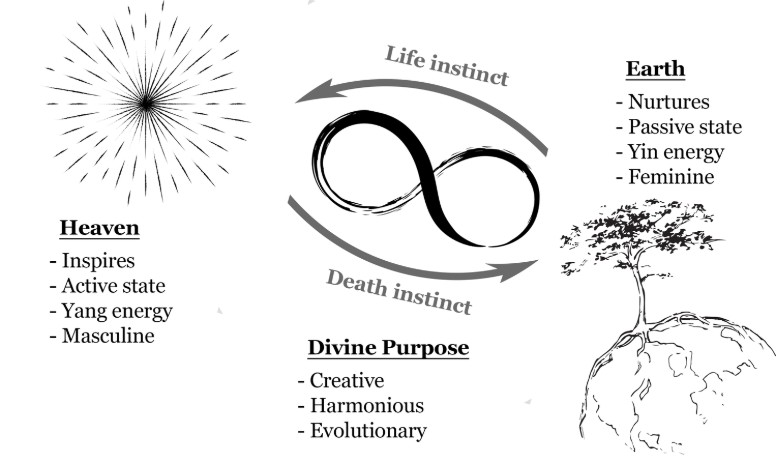

Take a tree, for example, which we can characterise in three ways:

- Earth: It is nurtured from beneath by rooting itself in the soil.

- Heaven: It is sustained from above by photosynthesising and growing toward the sun.

- Divine Purpose: It supports life by providing oxygen, food, shelter or even medicine.

Using the tree as an analogy, we see that humans are bound to this same process of development. We too must be supported by a source of nurture, must have a higher state to aspire toward, and so long as we are alive, must direct our life energy toward a creative purpose which contributes to our world. If any of these three elements are missing, we fall into ill-health and despair.

This dark, heavy state plagues us all on occasion, and lies at the core of every living being. Sigmund Freud, in his book ‘Beyond the Pleasure Principle,’ proposed that ‘the goal of all life is death,’ of which he is mostly correct. In reality, the goal of all life is death and rebirth. This is the endless cycle of the universe, where life is born, dies, and is replaced by new life forms. This process is balanced by opposing drives which constantly work together to achieve balance. Freud called one the life instinct, and the other the death instinct.

Figure 1: The actualisation of life. The tree, like any living organism, originates from a single point (Earth), growing from nothing to a higher state (Heaven), while playing out a divine purpose in its environment. Binding this process together are the opposing life and death instincts.

The life instinct compels us to survive, pursue pleasure, love and care for others, cooperate, reproduce, and self-actualise. The death instinct, in comparison, has a magnetic pull toward a desolate state which the life instinct must overcome. We all experience this when we struggle to get out of bed, or get caught in negative thinking, or procrastinate, or fall into apathy and depression. Behind these inhibiting acts of self-sabotage is the death instinct, continually working to return life to its original, inorganic state. However, so long as our basic needs for food, shelter and connection are met, and as long as we have a higher power to aspire toward, the life instinct can thrive — despite the pull of the death instinct. What Freud referred to as the ‘pressure toward death’ is then overcome, and our journey can progress. The only remaining concern we have is determining which direction this so-called life instinct should take.

Permission to grow

Our divine purpose is unique compared to other life forms, due to our ability to choose a higher power to model ourselves after, which we do through worship.

The definition of worship is: ‘adoration for a deity.’ Yet this does not fully capture it. Another way to define worship is: ‘the act of channelling our actualisation through another person or entity.’ This involves making ourselves completely vulnerable and defenceless, as well as identifying with someone or something which we believe can lead us to a higher state of being.

Furthermore, before we can begin the path toward Self-actualisation, we need to secure help. While a tree can anchor itself in the soil and grow toward the sun, humans need the support of other humans to grow to maturity. The world is complex and full of danger, and our True Self has infinite potential, while our body is limited — especially early in life. We start off helpless while overwhelmed with possibilities in an ever-expanding civilisation. Along with nurture, we need life presented to us in a structured way. We also need initiation into the world, which we gain by imitating specific role models within our ‘tribe.’ For this reason, we feel an instant pull toward people who we believe can show us the way forward; people of higher power who ‘have it all worked out.’

The original higher power

Regardless of whether you are religious or not, you have already given yourself over to a higher power. The second you came out of the womb, you were a frightened, vulnerable baby, with a desperate need for care and security. From this precarious position, anyone who cared for you became larger than life. These family figures were flawed, of course. Yet from your infantile perspective, they were magical beings from a divine realm, possessing qualities and abilities that were beyond your comprehension.

Consider that your experience back then was immensely different from now. For one, you did not possess the mind you now take for granted. Logic and knowledge were non-existent. There was no analysing and making sense of the world. Instead, you experienced the world energetically. An example which demonstrates this mode is a superhero movie, or any movie with a compelling protagonist. These transcendental characters are portrayed as supremely gifted, and hence morph into someone other-worldly. An underdeveloped mind views its parents precisely this way. Relative to a baby, consider the herculean strength of your father as he picked you up without effort. Imagine for a second your mother’s nurturing softness, and the intoxicating way her breast milk would have nourished your fledgling body. These paragons really would have been something to behold for a child.

When you reached your ‘terrible twos,’ you entered the narcissistic phase of childhood development, and your grandiosity peaked. You believed you were indestructible, and that the world revolved around you. Your vocabulary consisted mostly of ‘I,’ ‘me’ and ‘mine.’ You roamed your environment shamelessly, while there was always somebody taking care of your every need. Eventually, you hit barriers. As frustrating as it was, there was a gap between your perceived capabilities and your actual power. You realised that without someone to support you and cater to your needs, you would get nowhere. Due to your lack of real-world ability, you had no choice but to delegate power to your guardians. You noticed that food, clothing and toys appeared like magic, and you took for granted that they would keep coming. Where things came from and who made them did not cross your mind, nor did the thought that you would one day have to provide for yourself. Personal power would come later in life as you grew and developed. Meanwhile, your guardians reigned over your life. You allowed them to feed you, shelter you, clothe you, help you go to the bathroom, manage your bedtime, and tell you where it was safe and unsafe to play. It was a given that they ran the show. This act of surrendering your personal power is called infantilisation.

Infantilisation is a state of helplessness, a survival mode in which a child entrusts their guardian to look after their well-being. It is like a warm blanket that slips over someone and sheds them of agency as soon as they are in the presence of any figure of perceived higher power. When infantilised, a person unconsciously hands over the wheel for their life. It is like being ‘remote-controlled’ by the mind of another person. Here you have no agency except when the other person says so. In childhood, this is normal and expected. Whether the higher power is nurturing and loving, or neglectful and abusive, is irrelevant. The primary concern is survival, and therefore any higher power is better than none.

Infantilised and with no capacity to influence outcomes, the child reverts to using a crude psychological mechanism to establish a sense of control. Much like a binary switch, on one side is a state of absolute worship, and on the other, a total rejection of it.

Split to survive

Having no capacity to protect or care for oneself is terrifying. You will appreciate that for the child, abandonment equals death. This vulnerable position would have brought you face to face with the death instinct. When the death instinct arises, a child is gripped with terror. Life becomes black and white, meaning you lose the ability to see the nuances of a situation. Survival becomes your sole concern.

While some situations terrify more than others, the child can never feel entirely at ease. They remain acutely sensitive to stressors at all times. Also, at that age, the child cannot comprehend that their guardian might have stress in their life, have bad moods, or still be dealing with unresolved trauma. The child only knows that anger and neglect equate to danger.

To deal with the terror of being alive, we reverted to a binary view of the world. We abstracted our experiences to maintain tight psychological control, switching between a state of absolute loving, or pure loathing. We adored anything that we perceived as ‘good’ with all our heart, such as our family or favourite toy. On the other hand, we hated anything that we saw as ‘bad’ or that frightened us, which also included our family members when they were neglectful, unpredictable or abusive.

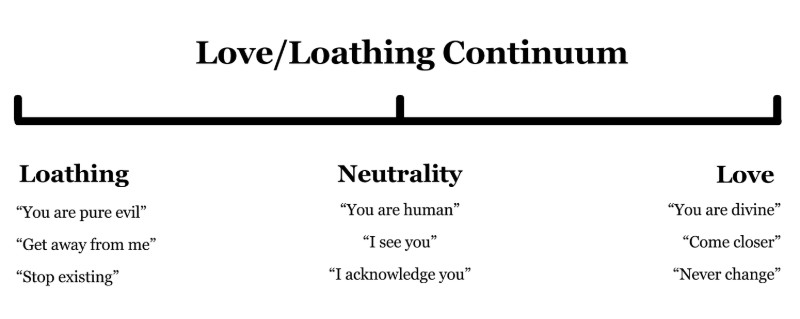

This polarised state can be represented on a continuum as follows:

Figure 2: The love/loathing continuum. Children, as well as adults polarised by fear, will alternate between two extremes to regain a sense of control. With loathing, one aims to psychologically annihilate a source of threat, whereas with love, they aim to merge themselves with a source of nurture and power.

For a child, neutrality is not an option. Life is black and white, all or nothing. When your guardian mirrored you, catered to your needs and helped you feel safe, you loved them with all your heart. This would have brought you closer to the life instinct; that warm feeling of safety and confidence which propels you toward Self-actualisation. When your guardian became angry, cold or neglectful, your death instinct activated instead, and you directed your rage toward them. This polarised state is why babies and children can turn to anger so unexpectedly, and then be instantly appeased and made calm again.

What Melanie Klein referred to as splitting gave you somewhere to direct the intense emotions which you could not process in your under-developed mind. It was vital for you to create a tyrant figure and focus your rage toward them. You did this to preserve what came to be a divine being, a loving and perfect figure who would never abandon you. Furthermore, by having a perceived tyrant to rage against, you could ‘empower’ yourself against the terrifying prospect of abandonment or annihilation. In the child’s mind, a person remains divine until they let the child down, after which they become the tyrant. In reality, your guardian was a person whom you experienced in polar opposite ways.

A word such as ‘annihilation’ might seem extreme to an adult, but in the child’s mind, it is a real possibility. The more abusive or neglectful a guardian is, the more overwhelming the terror becomes, and the more a child must split to cope. When situations feel frightening, the child clings to any sign of the divine being, thus helping alleviate their dread. In the child’s mind, this will protect them. In reality, the split is keeping the child sane.

The split is also why we are so strongly affected by heroes and villains in popular culture. By identifying with and worshipping the hero, we vicariously experience a sense of power, whereas the villain becomes the dumping ground for our negative emotions and fear of helplessness. The split is why we fantasise and project ideal situations and outcomes in our minds. It helps us cope with the unpleasantness of life. It also explains how parents often continue to hold tremendous sway over their children for decades, turning with one snide remark an otherwise independent and robust adult into a helpless infant.

The great parent

A fascinating effect of the split is the uncanny ‘quality’ it gives the people we project it on — above all our parents. Regardless of what we believe, nobody can deny that they have experienced this polarised state. We have all adored our heroes and role models to the point of obsession, or have found ourselves despising our loved ones or public figures to the point of utter disgust.

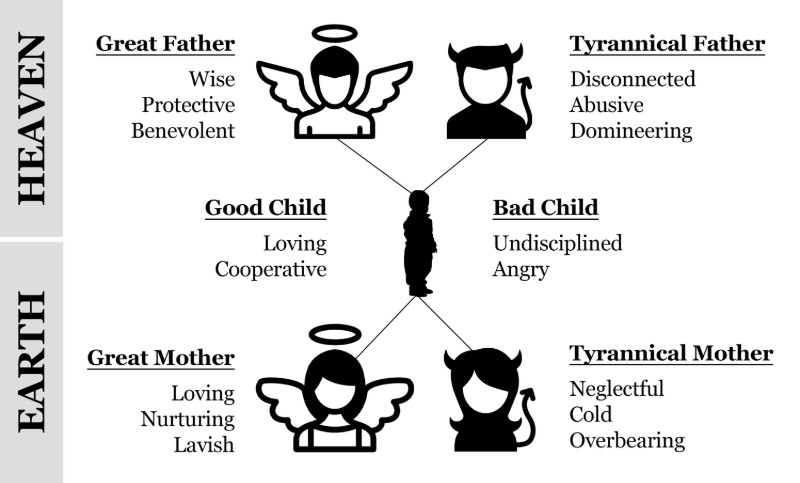

As already explained, a higher power is critical for our development. Losing it for even a second throws us into disarray. This is what gives parents such power. Like the soil nourishing a tree’s roots, or the sun shining above, our guardians play a fundamental role in our growth which permeates the deepest corners of our psyche. Helping them with this tremendous, life-creating responsibility are a set of archetypal energies based on Heaven and Earth. One represents profound wisdom, the other embodies boundless abundance. One provides structure, guidance and purpose, the other demonstrates the art of life. These masculine and feminine energies manifest in the psyche in the form of two archetypes separated by gender; the great father and the great mother.

An archetype is a blueprint handed down from our ancestors, which contains a pool of traits, points of view, abilities and energy forms. An example of an archetype is the warrior, who is aggressively strong and competent in combat and warfare. Another is the explorer, a restless person who is naturally driven to challenge the status quo and pursue the unknown path. The hero is naturally an archetype, being the person who rises to meet a challenge in order to make meaningful change. In their purest form, archetypes hold enormous potential, and they are within us all. However, because we are human, embodying their potential is a lifelong challenge which we never get right. It is no different for the great father and mother, both of which posed enormous challenges for our ancestors trying to embody them. The immense capacity of these two archetypes to nurture and support life was passed on from one generation to the other, until it was time for our parents to embody them.

First of all, the great mother and father archetypes are not limited to a person of the corresponding sex. A man can embody the great mother, and a woman the great father. Fathers can be affectionate and nurturing, and mothers can provide guidance and wisdom. Secondly, no person can be perfect in their endeavour to live up to these God-like figures. Nonetheless, they exist in every human being as latent energy waiting to be released when duty calls. From the point of our conception, these archetypes looked to express themselves through our guardians. When a parent recollects the moment their first child was born, they tend to describe a momentous shift. This is, in fact, the great parent archetype awakening within them. They sense themselves presented with a significant responsibility which calls on them to leave youthful pretence behind, and transform into the formidable figure their child needs them to be.

At its best, the great parent brings out superhuman qualities in a person, along with the ability to create a safe container for the child to grow and actualise. The guardian becomes wise, calm and supportive, able to attune to the child’s needs by drawing on the abundant powers coming from within. In the worst case, however, when the parent is traumatised, stressed or caught up in addiction, the great parent archetype transforms into the tyrant. The parent’s posture stiffens, their face permanently hardens, and their gaze sharpens. They use a combination of anger, disapproving stares, emotional coldness and shamelessness to enforce the image of authority and control. Some parents alternate between the two extremes in a split moment, lovingly channelling the great parent, until frustration tips them over the edge, from which they grow rigid and angry, unconsciously channelling the tyrannical parent. Other times, we project the tyrant onto our parents regardless of whether it is justified, as captured in the teenager who screams “I hate you!” when they fail to get their way, or the three-year-old who throws a tantrum.

The split also works the other way when adults are overwhelmed and insecure. When you were angry and uncooperative, your guardians experienced you as the ‘bad child,’ and when you were cooperative and loving, they experienced you as the ‘good child.’ Many parents even call their children ‘good girl/good boy’ and ‘bad girl/bad boy’ depending on the child’s behaviour, which is the parent’s split in action.

Figure 3: The split dynamic between a child and their guardian/s. The figures which arise from the split are enigmas, uncanny ‘spirits’ from another realm. When the energy of the great or tyrannical parent expresses itself through our guardian, however, it becomes quite real. The great mother offers a source of nourishment for the True Self via the Earth realm. The great father is a north star or lighthouse who leads us to our Self-actualisation.

In childhood, you looked to the great mother for yin energy, a passive force which regenerates and sustains the soul. The great mother held you safely in her womb, then nurtured you once you were born, caring for you and helping you feel secure. Through the yin energy of the great mother you were able to rest in being, and so align yourself with the harmonious flow of life energy. Later, you connected with the great father; a figure who could provide structure and protection. His role was to help you channel yang energy, an active force for penetrating and impacting the world.

These two enigmatic archetypes dominated your psyche, and you yearned for them as the figures who would shield you from the terror of life. Your later expectations of them depended on your experiences with your carers, which began with your guardians, then extended to older siblings, uncles and aunties, teachers and any other adult of perceived higher power. Each person contributed toward your idea of what the great mother and great father archetypes encapsulate. For example, if your father was short-tempered and angry, you would form a picture of men as being more tyrannical than benevolent. If your mother was emotionally closed off, you might see women as cold and difficult to please — a source of shame and rejection. Such experiences remain firmly planted in your psyche for the rest of your life as paternal complexes, which the Jung Lexicon defines as ‘a group of emotionally charged images and ideas associated with the parents.’ These are activated and projected onto anybody you perceive as more powerful than you, which helps explain why we often feel fear and uncertainty around people of high status or beauty. Their apparent perfection associates them in our minds with the frustration and pain of trying to obtain the love of the great parent. These deeply entrenched complexes can cripple us and render us helpless. They also influence our relationships moving forward, and as much as it can feel like it is the person who is triggering these emotions, it is in fact our split activating, along with flashbacks of past experiences with the great mother or father.

From splitting to worship

Due to your precarious position, you had no choice but to split and project onto your guardians the archetype of the great parent. The alternative was unthinkable; the tyrannical mother or father could annihilate you. As a result, you infantilised yourself and worshipped your guardians. In your developing mind you looked up to them, hoping they would use their power to support you, inspire you and mirror back your divine nature. When you ran out to explore the world, you looked back on occasion to make sure they were still there watching over you. In turn, you observed them and imitated their actions. You shared your smallest successes with them. Their approval was everything, and their disapproval crushed you.

Because they were ‘perfect,’ their word was gospel. Consequently, their anger and disapproval could never be their fault; it had to be someone else’s. To blame the great parent would be to risk losing your source of nourishment and safety. So you focussed your rage and negative feelings toward the tyrannical parent instead. How your guardian handled their alternating position as the great parent and tyrant would play an enormous part in your growth and future relationships. Such is the power of the split. Such is the power of anyone we worship.

This early tendency to externalise our source of higher power gives others a license to set us free, or imprison and control us. Behind our surrender lies the enigmatic great parent, setting the stage for every future relationship, running deeper than we could ever imagine. Society feeds off our split in numerous ways. Celebrities project an image of perfection, and we unconsciously see them as a higher power. Monarchies maintained a firm grip over whole empires for centuries in the same way by projecting divinity. Dictators, through fear and cult of personality, also capitalise on this phenomenon. On a smaller scale, the split is responsible for the halo effect, which is when we exaggerate a person’s goodness and wisdom based on their appearance and body language, becoming putty in their hands while doing our best to please them. A lesser-known but common form of the split is when we meet someone who reminds us of our parents in particular ways, wherein we feel ourselves unconsciously drawn to them in a childlike way.

Whoever can project the illusion of high status and grandeur can awaken our inner child and therefore hijack our personal power. The woman or man of stature, strength or undeniable beauty, the celebrity, the politician, the charmer, the social media influencer; anyone can activate our split and gain our worship, or at least our curiosity. It is easy to forget the intended purpose of the split, which is to maintain psychological health long enough for us to come of age. Easy to lose sight of is our divine purpose, which is Self-actualisation. The goal is not to forfeit our personal power to others, but rather to use worship as a launching pad for our growth, with the result being the constellation of a competent and fully-developed Self.