The Narcissist’s Kaleidoscope Of Faces

Three things cannot be long hidden: the sun, the moon, and the truth.

- Buddha

What makes narcissists so insidious is that they do not always fit the DSM-5 criteria of ‘inflated self-esteem, lack of empathy, demanding of attention, and sense of entitlement’. A narcissist can come across as needy, desperate, appeasing or apologetic. They can seem warm and loving, with a deep desire to connect. They can forfeit the spotlight, and declare how wonderful you are. They can then act from the shadows, inflicting harm and punishment on you in horrible ways. They can be brazen, reckless and treat people like pawns, manipulating, cheating and lying at will. They can be one person in front of strangers, and someone else entirely at home. And even with you, they can be one person one second, and switch suddenly. This can be utterly crazy-making, as the tender, charming person who attracted you morphs into a cold, sinister, rage-filled monster. It is as though they are many people in one. The truth, sadly, is not far off.

It can be easy to forget that behind every polished narcissistic facade lies a fractured soul. Whether it was through abuse, neglect or having to live up to an inhuman ideal, the outcome remains the same — self-abandonment, avoidance of pain at any cost, and a burning sense of low self-worth.

Sometimes the grandiosity defence is not enough to compensate for this. The world is harsh and unpredictable, and reality often comes knocking on the narcissist’s door. When their false self inevitably fails them, the narcissist needs to adapt. For that, they have an array of alternative ‘selves’ to get their needs met, defend against re-traumatisation, and punish those who hurt them.

The typical narcissist is not out for world domination. Narcissism has one purpose; garnering narcissistic supply. Supply props up a false self. This false self is the tip of the spear which penetrates the world while defending the narcissist’s wounded core. But what about the rest of the spear? Those who carry Complex-PTSD are themselves also complex. They can be dissociated and paranoid, moving between conscious states like a dream to navigate their tangled web of wounds. Often they do not aim to hurt others, but rather act out of desperation. Other times, however, they do aim to hurt others, for which there is an insidious reason. More on that shortly.

To brush someone off as a narcissist without widening your lens is to miss the bigger picture. This can leave you uninformed at best, and exposed and vulnerable at worst, as someone you perceive not to be a narcissist might be presenting one of their many alternate ‘faces’. To educate and arm ourselves, we therefore need to delve into the world of personality disorders to get the entire picture.

The narcissist’s hidden army

To maintain a continuous, harmonious sense of Self, a person must have their core emotional needs met. Like a smoothly-running engine, any breaks in those needs, and the entire system splutters and eventually collapses.

C-PTSD not only disrupts a person from getting their core needs met, but also irreversibly fractures the Self. This culminates in a family of core wounds which reshape the child’s beliefs about themselves and the world, and cripple their capacity to thrive. As a result, pain emanates from the child and permeates every facet of their experience. They get a constant sense that ‘something’ is wrong with them. These unbearable pulses from within are the Self signifying that its core needs system is damaged and requires some kind of resolution to stabilise it. The core needs, their respective core wounds, and the accompanying resolutions are outlined as follows:

| Core Need | Core Wound | Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Love | I am unloved | I am loved |

| Connection | I am abandoned | I am connected |

| Resilience | I am weak | I am strong |

| Significance | I am not enough | I am enough |

| Acceptance | I will be rejected | I am wanted |

| Legitimacy | I am bad | I am good |

| Worthiness | I am unworthy | I am worthy |

| Safety | I am unsafe | I am safe |

| Visibility | I am unseen / unheard | I am seen / heard |

| Competence | I am stupid | I am capable |

| Growth | I am stuck | I am developing |

| Desirability | I am undesirable | I am desirable |

Figure 2: The core needs/wounds table. The C-PTSD core consists of a series of unmet needs, the pain associated with them, and the resulting limiting beliefs.

Core wounds quickly become intolerable, and must be resolved by any means necessary. Robbed of a stable experience to call ‘Self’, the child begins a frantic effort to ‘patch up’ these gaps, gradually stitching themselves together using various compensation mechanisms. For this crucial task, the human mind has a series of tools to help maintain psychological balance and ward off insanity. The traumatised child restores the integrity of their Self and gets their core needs met using measures such as amnesia, deceptiveness, seductiveness, aggression, paranoia, fantasy, fiction, provocation and more. These coping behaviours manifest in the form of various ‘protector’ personalities, which ease the pain of the child’s core wounds and help them temporarily find the required resolutions, both real and imagined.

The protectors act as allies who get needs met and defend against psychological pain. These personalities exist in all of us, activating during times of stress, yet become especially pronounced and dysfunctional in response to C-PTSD. In their most extreme forms, they take over a person entirely and become personality disorders.

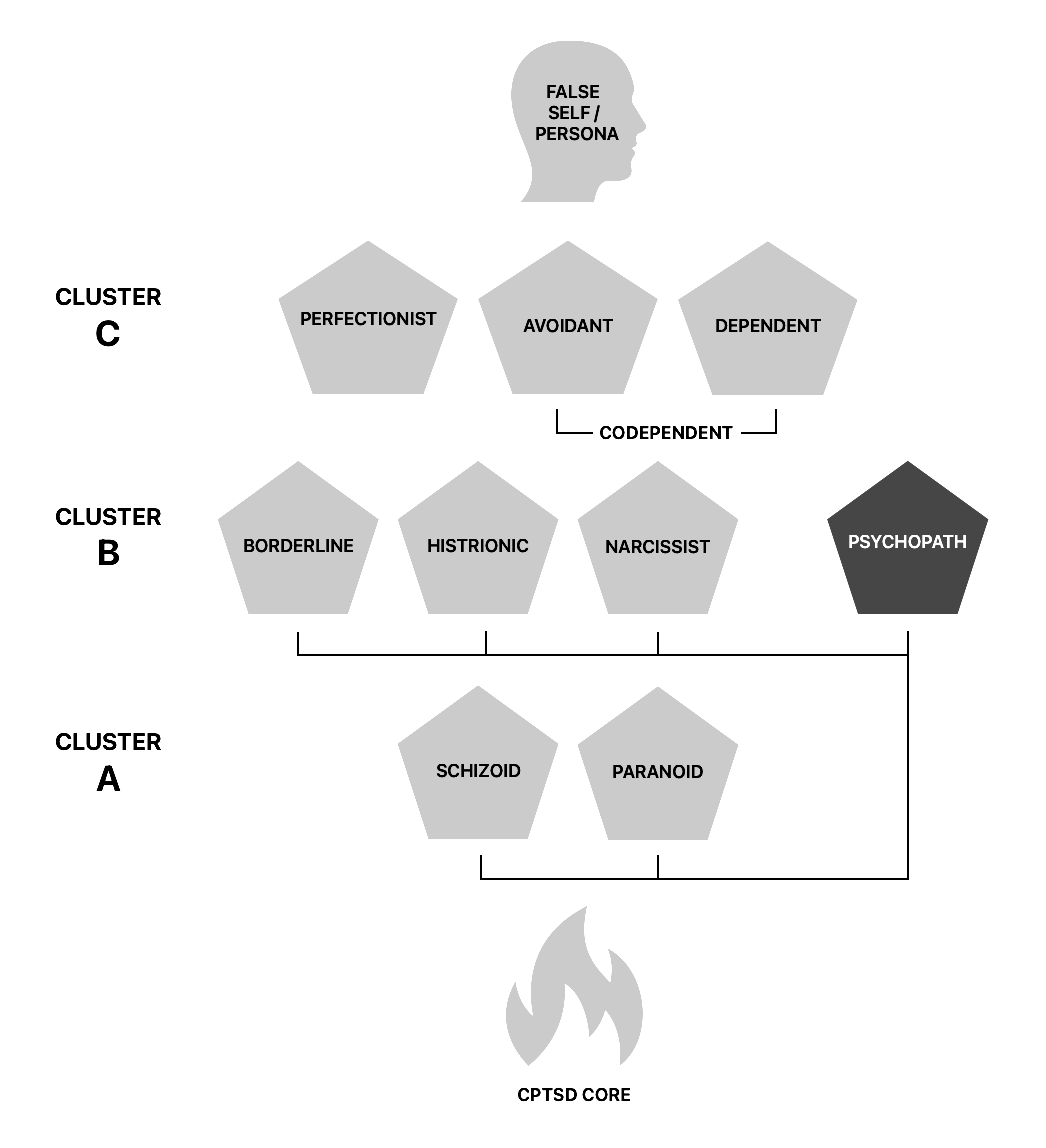

Figure 3: The protector personality map.

The protector personality map demonstrates how narcissism lies among numerous C-PTSD states. The primitive and passive ‘cluster A’ personalities are closest to the core and protect against threat. ‘Cluster B’ forms the active or ‘dramatic’ states which aim to garner narcissistic supply, seduce, achieve goals, defend against hurt, and of course, get core needs met. ‘Cluster C’ states aim to calibrate closeness and control in a relationship to ensure a sense of security and order.

The protector personalities are as follows, with each one moving progressively further away from the trauma core:

Schizoid

Seeks: To escape reality.

Fears: Exposure.

The first line of defence to the terror of neglect and abuse is to dissociate, or ‘check out’ of reality. The schizoid sees the world through a psychological window. They feel numb to their humanity, never able to absorb the entirety of their experience. They appear aloof or distracted. The schizoid has one foot in reality, another in imagination. They can spend vast periods of the day fantasising and imagining great successes, escaping their life and going somewhere else, doing something better or being someone new.

Schizoids can be creative, since they have a unique ‘outsider’s’ perspective. They can think laterally, and their mind goes places the normal person’s rarely would. The narcissist draws on this state for their grandiosity, leaning heavily on it to defy reality and imagine themselves as superior and great.

The schizoid has a flat emotional affect and an apparent indifference to people’s opinions. A low-level enthusiasm might come to them, but it quickly fades. They prefer solitude over the company of others. The schizoid might take over after a relationship breakup. In such cases, the person might isolate themselves, become asexual, or avoid social engagements for an extended period.

When narcissists are exposed, humiliated or have their supply suddenly snatched away, the schizoid might activate to help them cope. Narcissists also grow more schizoid as they age, becoming progressively more reclusive. This is usually brought on by dwindling narcissistic supply and resentment, as their self-centredness and exploitation push people away. In response, the narcissist channels the schizoid into their grandiosity to avoid the shame of isolation, declaring that they much prefer their own company over wasting their precious time on others.

Paranoid

Seeks: Emotional and physical safety.

Fears: Threat to emotional and physical safety.

The paranoid is convinced that someone is out to get them. They believe the person walking behind is following them home. The people in their lives are manipulative and plotting to abandon them, humiliate them, use them, even to poison them. Although they have no proof, the paranoid is convinced that their partner is incessantly cheating on them. They perceive betrayal and threat at every turn while being convinced that it has already happened. If someone is not at their phone or is out for too long, they must be up to something. Trust is fickle in the paranoid’s life. They have difficulty forgiving others, and have a tendency to hold grudges.

Trauma is enough to trigger anyone’s paranoia and leave them on the constant lookout for threats, with their fight/flight system ringing at maximum level. Making matters worse is that many dysfunctional households harbour dark secrets and duplicity. Wounded and abusive parents often lie, withhold information and manipulate in the shadows to avoid accountability, causing the traumatised child to internalise mistrust as a permanent state of mind. The paranoid lingers beneath the surface as a constant suspicion, but takes over during times of stress. This can cause the traumatised person to lash out or even cut off relationships suddenly.

Paranoia often originates from real threat and betrayal. Hyper-vigilance is a useful energy for pre-empting abuse, testing reality, and ensuring we can trust others to mean what they say and do what they promise. Yet when it becomes a permanent state, paranoia can make deciphering reality and truth extremely difficult. A person with a paranoid protector will often attract someone with a personality disorder, who might act deceptively and dishonestly to avoid abandonment or the shame of accountability. It is a vicious cycle. Dysfunction breeds lies, which breed mistrust, which breeds fear of abandonment, which breeds further dysfunction, and the cycle repeats.

Borderline

Seeks: Love and emotional regulation.

Fears: Abandonment and emotional dysregulation.

The borderline is the first active protector personality, which is telling, since the name describes a person on the borderline of sanity and psychosis, between control and chaos, capable of falling head-first into panic, fury or depression at any time.

The borderline is prone to experiencing most of the core C-PTSD symptoms, and so suffers greatly. Their solution for this is to seek out the perfect love, aiming to regulate their inner turmoil through an ‘ideal’ partner. By establishing love with the perfect person, the borderline can calm their fear and alleviate their suffering through a bright future with a beloved who will never leave them.

The borderline is prone to splitting, seeing people as all-good or all-bad. When they polarise in the positive, they will attach to that person at warp speed. At first, the borderline idealises their partner. The relationship is the most amazing thing that has ever happened to them. Their partner is a dream come true. This love will manifest into a bright future filled with abundance and prosperity.

However, no fantasy can withstand the test of reality for long. Within the first few weeks or months, the partner’s flaws come into focus, and cracks appear in the illusion. The trauma resurfaces and challenges the split. To help the borderline fend off the resulting discomfort, they externalise their feelings and blame their partner. ‘All-good’ flips into ‘all-bad’, and the ‘devalue’ phase begins. The borderline criticises, judges, shames, punishes and ‘points out’ the partner’s flaws. Nothing the partner does is ever good enough.

The main traits of the borderline are:

- Abandonment anxiety: The borderline clings to others, demanding their constant time and attention to feel secure in the relationship.

- Fusion: The borderline only feels secure when completely enmeshed, hoping to have the other person co-opt responsibility for their emotions, thoughts and decisions. It is only a matter of time, however, before they lose their sense of Self and feel engulfed by the other person.

- Approach/avoidance: The borderline seeks fusion with others and simultaneously has abandonment terror. Any perceived break in their fantasy of perfect love triggers their abandonment anxiety, and with it, threatens their mental stability. Therefore, if the other person disappoints the borderline, acts independently, or creates emotional distance, then the borderline pulls away abruptly as a defence. They go through phases of being deeply connected and in love, before suddenly growing cold and critical without warning. While this may produce a short-term feeling of control, the borderline’s fear of being alone compels them to re-engage, and they cling to the other person again. Before long, they feel engulfed and again pull away. The resulting push/pull dynamic naturally results in constant blow-ups and fights with the confused loved one. The relationship then becomes plagued by arguments that lead nowhere, emotional outbursts, bitterness, mood swings and chaos.

- Fluctuating self-esteem: The borderline will alternate between supreme confidence and crippling self-doubt and self-loathing.

- Identity diffusion: The borderline has a weak sense of self and constant self-doubt. They have an unclear, shifting self-image, changing their values and behaviours as necessary to be accepted.

- Chronic emptiness: A hollow feeling of emptiness is a C-PTSD symptom against which the borderline has little internal defence.

- Emotional lability: The borderline often drowns in their emotions. They experience extreme shifts in mood, and can bounce between intense euphoria and terrible depression. They are often unsure how they feel about others, and are prone to suddenly and abruptly ending relationships. They have weak impulse control and demonstrate risky, reckless behaviour. They tend to hold in their chaotic emotions, desperate to stay ‘normal’ and not hurt others, until they erupt suddenly in a violent rage, throwing temper tantrums and acting out in ways they later regret.

- Self-harm: Borderlines are known to self-harm through cutting, abusing drugs, binge-eating and promiscuous sex.

- Suicidal ideation: The borderline skirts the edge of the death instinct, sometimes playing with the idea of suicide as a way to end the torment.

- Dissociation: The borderline experiences gaps in their memory. They sometimes derealise and lose touch with reality, feeling like overwhelming events are happening to someone else, especially when they are shame or guilt-inducing, such as when they cheat on or betray someone. They might create a fiction to compensate for their amnesia, hoping to keep a ‘sane’ storyline to avoid abandonment or going over the edge.

The borderline struggles with arrested development. Therefore, playing the helpless child or victim comes easily to them. The borderline makes themselves submissive in the presence of others, hoping that person will take up the saviour or parent role and magically rescue them or solve their problems. They struggle to form horizontal adult-to-adult relationships. Their innocence and playfulness are endearing to people the borderline comes into contact with. If someone has a latent saviour complex or harbours covert narcissism, they will gravitate to the borderline and pick up the slack. Such people are more than happy to play the role of the ‘perfect’ partner.

The borderline’s splitting and magical thinking aim to shield them from their trauma. The borderline is constantly vigilant, perceiving abandonment and threat at every corner, and because of this, acts out in ways that ensure abandonment. They are forever testing their loved ones, pushing their sore points to check if that person will stick around. Together with their approach/avoidance cycles, the borderline puts others on constant edge. The other person has no idea when the borderline’s mood will switch, or when and how the borderline will accuse them, judge them, criticise them or simply erupt and act out. The person usually has no idea they are being put through a washing machine of splitting, paranoia and repressed anger.

Histrionic

Seeks: Attention.

Fears: Rejection.

It is natural to want to be desired. However, when this need fuses with C-PTSD and narcissism, the results can be devastating.

The histrionic craves attention. They are often attractive, sexual, vain and overly concerned with their appearance. They objectify both themselves and others, believing that to be worthy of love, one must be desirable. The histrionic therefore seduces people into giving them what they want by having an irresistible appearance and energy. They may also act overly dramatic or provocatively to garner attention. They often say things that polarise or shock to get someone’s attention, even reverting to wild accusations. For example, they might declare: “You don’t love me. You don’t care about me.”

The histrionic needs constant reassurance and approval, and hates to be alone. They want to be complimented regularly and be the centre of attention. When it becomes your turn to speak, however, their attention often wavers. They panic when you do not respond to their communications immediately, and then try to provoke a response. If they do not get the attention they crave, they will act quickly, often flip-flopping their emotions, going from victim, to angry attacker, to passive-aggressive, all in the hope of forcing you to engage them.

The histrionic regulates their self-esteem with attention. They flirt naturally and effortlessly, and prefer the company of the opposite sex, often using them for gratification. They might also turn the conversation to sex at unexpected moments. Their need to feel desirable can lead to triangulation, where the histrionic introduces a sexual threat into their relationship dynamic, hoping to provoke their partner’s jealousy. When the partner is not showing enough affection and desire, the histrionic triangulates to ‘remind’ their partner of how desirable they are. They might even go as far as flirting with another person in their partner’s presence while denying their true intention, claiming it was ‘just being friendly’.

In extreme cases, the histrionic may damage their own property or fake a crisis to get their partner to come to their rescue, or hide something to force their partner to solve the ‘mystery’. In relationships, they usually want to move in together quickly. They have a high moral code, but rarely live up to that standard. They are quick to call out others on social and racial justice issues, but only do this to appear self-righteous and draw attention to themselves.

Psychopath

Seeks: Revenge and power.

Fears: Humiliation or failing to get their way.

What would you do if you had no emotions, no empathy and no conscience to hold you back? Would you steal, cheat, and manipulate? Would you lie to your loved one’s face if you thought it would benefit you? Have you ever found yourself on the verge of doing something ‘immoral’ toward someone, imagined the rush of power it would give you, before suddenly holding yourself back?

The term ‘psychopath’ comes with enormous stigma. People typically associate it with mass murder and inhumanity. However, we need to overcome this stigma if we are to understand it, and above all, spot it in those who are lower on the spectrum. Inside all of us is the seed of the psychopathic self, waiting to flower under the right circumstances.

The psychopath is the fixer and equaliser. The one who cleans up the mess and gets things done. The one who could not care less, who gets a rush of power when having their way with someone. They lurk in the shadows, paying close attention to the world around them. Meanwhile, they keep a black book of ‘misdeeds’, waiting for the perfect time to strike and deliver their revenge. The psychopath adheres only to the law of the jungle, where the strongest survive, and the weak and naive get what they deserve. For the psychopath, any means justifies the end. They take pleasure in dishing out revenge for perceived slights, and have a tendency toward humiliating others and exploitative, sadistic sex. The malignant narcissist acts mostly from their psychopath, often with no remorse or empathy.

Vindictiveness comes easily to the psychopath. The psychopath deflects and blocks out the inconvenient truth, and lies compulsively. They do everything in their power to achieve their ends, which includes avoiding abandonment or exposure. The only thing keeping us from activating the psychopath in its horrific power is our conscience, which we channel via our True Self. Without our inner compass and outer environment to keep us accountable, there is no telling what we might do. There is a reason why many of the highest positions in our social hierarchy are occupied by fully-fledged psychopaths. Unhindered by their conscience, the psychopath forces their way to the top, and while at the top, becomes even more psychopathic due to a lack of accountability.

The psychopath is the strongest card the narcissist has to defend against the spectre of psychosis. The psychopath is a judge and executioner. Faced with disrespect, humiliation or insult, they punish others to restore balance and ensure justice, waiting for the perfect moment to strike, which might be months or even years in the future. The narcissist carries immense shame and feelings of low self-worth, and so the psychopath supports them in offloading those feelings to others in a way that avoids accountability. The psychopath will covertly attack others on behalf of the traumatised individual. In extreme cases, the psychopath will become violent.

If a person’s conscience does arise to counter the psychopath’s malignant behaviour, the psychopath blanks out their memory and denies everything. The psychopath creates fictions to cover up their behaviour and avoid accountability. They have no morality or plan, often acting on the whims of the moment.

The psychopath is always lurking. If the target finds themselves suddenly reeling and shocked, caught utterly off guard, it is often the psychopath who has plotted and executed their plan with utmost prejudice. When someone becomes wholly detached from their True Self, they embrace the psychopath as a default state. The further up the spectrum they move, the less their conscience is there to stop them. Many narcissists, histrionics and borderlines can drift in and out of the psychopathic state during times of stress or threat, although this does not last long. In the borderline’s case, they often experience guilt and shame for their actions after the influence of the psychopath wanes.

The psychopath is hyper-competitive. They take the narcissist’s need for attention and status and pursue it to the fullest. The psychopath will torture their loved one on behalf of the borderline to ensure the loved one remains small enough to control, hence losing the confidence to leave. The psychopath, through the histrionic, will flirt, seduce and pursue a desired person without shame, even in the presence of their partner, often for mere revenge. This often causes immense destruction to the relationship, but the psychopath does not care. These actions are carried out in the heat of the moment. The person is simply not present when the psychopath takes over.

All for one, one for all

Trauma is like the Earth’s core, and the cluster B protector personalities form the outer shell. The C-PTSD core remains tightly packed as the pressure of the real world threatens to break through and expose it. Abandonment, betrayal, engulfment and abuse, perceived or otherwise, all pose threats, forcing the relevant protector to emerge.

There is no guarantee, however, that a narcissist will demonstrate all of these states. Some will be more dominant, and others may not show up at all. It depends on the narcissist’s personality and the nature of their injuries. The more extreme the original wound, the more likely it is that all of them will emerge, especially the psychopath. When they are in their charm mode, the narcissist can be hiding any of these protectors behind their false self. It is only when your attachment to them grows and your defences lower that the cracks in their polished armour appear. Yet when push comes to shove, it is the psychopath who emerges to take charge, doing whatever it takes to protect the narcissist.

As you may have noticed, the cluster B personalities often overlap with narcissism. The borderline can be hot and cold, just like the narcissist. The histrionic is self-absorbed, and wants to look good and draw all the attention. The psychopath is callous, lacks empathy and has no issue exploiting others for their own gain.

This is not by coincidence — the many sides of the kaleidoscope are connected to the same source. The protectors all have the same core trauma, and need each other to achieve their objectives. For example, the borderline needs love, and if making themselves seem desirable or superior gets it, then they will do it.

The protector personalities also come in all configurations. While one protector might dominate, human beings are unique, and so are their adaptations to trauma. You can have a grandiose borderline, an emotionally-labile narcissist, a histrionic narcissist, a psychopathic borderline, and so forth.

When protectors fuse, they override symptoms of the others, making it difficult to diagnose. For example, a narcissistic borderline will experience a more stable sense of self-esteem through their narcissist protector, will not experience suicidal ideation, and will not self-harm. However, they may still experience emotional lability and maintain their fear of abandonment. Using this model, we can pull back from our narrow view and learn to see through a cluster B lens instead. Toxic is toxic, regardless of how it shows up. Rather than grow confused by a person’s haphazard behaviour, we come to expect any of the behaviours, from any of the personalities, at any time.

The histrionic and borderline tend to be attributed to women, and the narcissist and psychopath to men. Yet all protectors can exist in both sexes, and will merely express themselves with the flavour of the person’s gender and personality. Love bombing applies across all of the cluster B types, with the narcissist, histrionic, borderline and psychopath all looking for immediate and intense attachment in order to gain supply, attention, love or control, respectively.

Emotional instability also overlaps. The histrionic will be upset at not getting the attention or reaction they want. The borderline reacts negatively to perceived abandonment or because their idealised image of the other person is threatened, and they need to take out their uncomfortable emotions on someone. The narcissist, of course, reacts with rage when narcissistically injured, made to feel inferior or when their false self is attacked or discredited.

Environment determines fate. A person might alternate between protector personalities daily, depending on the needs of the moment. A protector might be stable and dominant most of the time, such as in the case of a grandiose narcissist. A protector might arise unexpectedly during conflict, before the default personality reasserts itself. If the power dynamic in a relationship shifts in the target’s favour, the narcissist might revert to a borderline state, as their grandiosity shatters and fragments of their True Self rise to the surface. During a crisis or breakdown, a protector personality might collapse and give way to another, more primitive defence. A default protector might also fall apart as a person ages and their power in the world fades.

Codependency: The avoidant/dependent dance

Unable to find inner balance and confidence alone, the traumatised person develops an over-reliance on relationships to regulate themselves and define who they are. This is a recipe for disaster, as paranoia, splitting, dissociation and other C-PTSD symptoms make maintaining a harmonious relationship nearly impossible. The traumatised person is constantly overwhelmed by negative emotions, and projects them onto others to help them cope. The battlefield in such dysfunctional relationships is attachment, where a struggle ensues for that elusive sense of safety, security and love.

All of the insecure attachment styles struggle with boundaries. Anxious people, having experienced precarious connection, require consistency above all. By completely dissolving boundaries, the anxious person hopes to fuse with their loved one, gaining constant and predictable access. Avoidant people feel unsafe with intimacy, and put up strong boundaries to feel safe. Fearful people flip-flop between both modes on a dime, dropping all boundaries and connecting deeply before brutally raising their shields without warning. An insecurely-attached person forgets where they begin and the other person ends. The other person’s needs either become theirs or become a threat. This painful, dysfunctional way of relating is codependency.

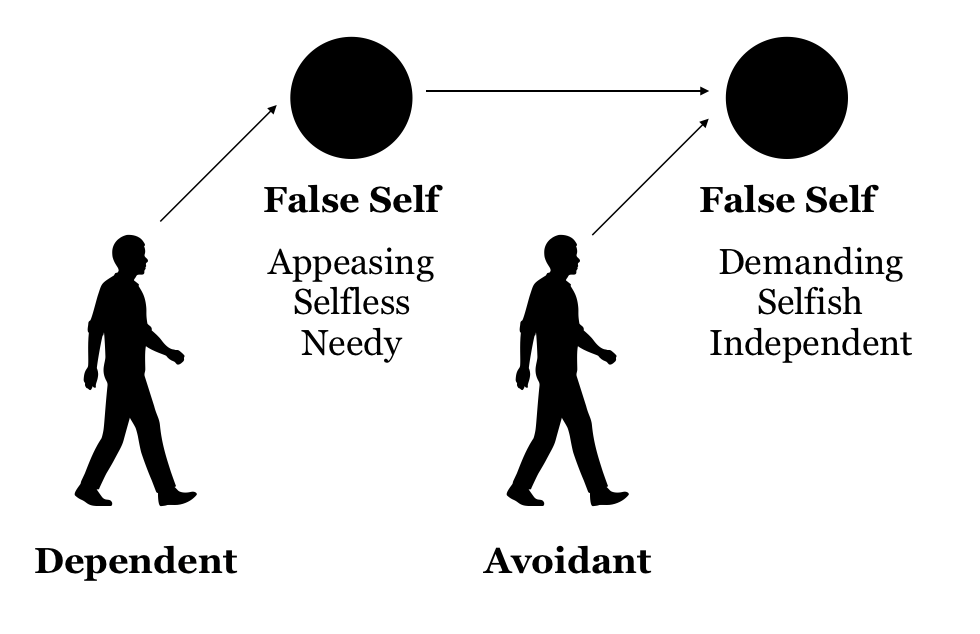

Since intimacy creates vulnerability, the potential of being hurt is too much for the insecurely-attached, which leads to a constantly see-sawing relationship. The dependent leans anxiously into the relationship, while the avoidant pulls away. The dependent directs their love outwards toward the other person, while the avoidant directs their love inwards toward themselves as grandiosity. The fawning dependent is often wide-eyed and clingy, the avoidant is aloof and appears arrogant. The dependent tends to devalue themselves, while the avoidant over-values themselves to maintain separation. Both personalities are shame-bound, compensation strategies for trauma.

The dependent is overly reliant on the relationship to regulate their self-esteem and sense of safety. Because they feel like they need others more than others need them, they tend to become overly giving and sacrificial, hoping it convinces others to meet their needs. The dependent usually puts up with the abusive and destructive behaviour of others, too terrified to lose their loved one and face being alone. The relationship is all that is keeping the dependent from falling into their chaotic borderline state, where paranoia, panic and emotional dysregulation await them.

Although it seems on the surface like the dependent is simply being nice and giving, there is a darker side to this protector. Behind their submissiveness, the dependent is passive-aggressively demanding. By sacrificing everything for the relationship, the dependent creates a hidden contract with their partner; I will give to you unconditionally, and you will love me unconditionally.

The dependent leans on their loved one no matter how badly they are treated. They grit their teeth and bottle up their pain at not being seen or ‘respected’ for what they do, smiling through thick and thin to maintain their ‘perfect’ appeasing front. In doing so, the dependent ensures that their loved one both takes them for granted, and is never accountable for their actions.

Even from their submissive position, the dependent’s behaviour gives them a feeling of control. As the dependent fulfils the other’s every need, the loved one feels progressively more guilty and obligated to remain with the dependent. Leaving someone who sacrifices everything for you makes you a horrible person, after all. The loved one has little awareness that these feelings exist, due to the hidden contract being enforced upon them by the dependent. Also, by casting themselves as the ‘saviour’ who always comes to the rescue, the dependent hopes to gain the moral high ground in the relationship.

Such a boundaryless relationship is unsustainable, however. The need for safety comes hand in hand with a need for autonomy. A person requires firm boundaries to know who they are, and must defend the integrity of those boundaries if they are to grow and actualise. Yet the insecurely-attached person is not equipped with healthy boundary setting. Something has to give. The result is a push/pull dynamic, as one person steps into the avoidant role, and the other into the anxious dependent role.

To feel safe, one person leans toward the other for love. The other person, feeling engulfed, then pulls away to restore their sense of autonomy. The person who leans in then feels rejected and unsafe, and doubles down on their neediness, causing the other person to pull away even further. This causes immense hurt, and the dependent person finally gives up. The avoidant person, now feeling the pain of separation, grows anxious and leans in, and the cycle begins again.

This exhausting game is never resolved, since one person only feels safe with closeness, and the other person only ever truly feels safe with autonomy, albeit temporarily. Injecting chaos into this dynamic is the fearfully-attached person, who not only exhibits the predictable push-pull dynamic, but also an unpredictable response when their trauma is triggered.

In this codependent dance, the partners can flip-flop between the anxious and avoidant roles, other times the roles stay firmly fixed. Narcissists generally remain on the avoidant side, while their partners tend to be dependent. Behind this dance is a fear of abandonment and fear of engulfment. The codependent relationship is therefore a classic breeding ground for narcissistic abuse, where the narcissist attracts a target with a dependent personality. Both are playing roles which betray their authentic selves. The narcissist’s false self is grandiose, and the dependent’s submissive false self worships the narcissist’s false self.

Due to their neediness, a dependent person is instantly at a disadvantage in the relationship power balance. Their partner is ‘high value’, and they are the ‘inferior’ one. The dependent generally enters a relationship with low-self esteem, which creates the need to prove themselves to their ‘superior’ partner. This shifts the power balance in the narcissist’s favour, which allows them to take advantage of the desperate and needy partner. As these two people progress in an enmeshed state, a natural hierarchy ensues. One has the high ground, the other the low ground. Narcissists naturally thrive in such an environment, where the power imbalance gains them easy access to narcissistic supply. Yet the dependent partner is not innocent in all this. The narcissist exerts overt, hard power, while the dependent exerts covert, soft power.

Figure 4: The narcissistic, codependent relationship dynamic. As the power balance shifts, the avoidant becomes progressively more narcissistic, drunk on their power over the dependent.

Soft power includes people-pleasing, submissiveness and charming or appeasing the other person, all of which obligate them to stick around. Hard power includes ordering the other person around, yelling, threatening, ridiculing, shaming, dominating and directly controlling the other person. Typically, a narcissist will use soft power at the beginning of their relationship with a dependent partner, then revert to hard power when they feel threatened or sense the other person has sufficiently become attached.

At some point, the dependent will feel scorned and upset with the narcissist’s constant use of hard power and selfishness, and will apply hard power of their own while threatening to leave the relationship. The narcissist senses the end and reverts immediately to soft power. Once the relationship is restored and the dependent is appeased, the narcissist will switch back to being selfish and harsh. This is what lies at the core of the narcissist/dependent relationship dance.

In the case of long-term relationships, a codependent style will typically dominate, especially after a drawn-out power struggle, where the ‘house-broken’ person loses their willpower and comes to accept their submissive role.

The perfectionist

Due to their sense of Self being shattered into countless fragments, the traumatised person grows hungry for structure and order. The perfectionist personality is an antidote for this, where a person:

- Becomes overly preoccupied with setting and maintaining rules.

- Becomes obsessive-compulsive about how and where things should be.

- Sets impossible standards for themselves and others.

- Develops a rigid morality, and a heavy-handed set of ethics and values, based on the needs of their wounded self.

By becoming dictatorial in their rule-setting, as well as self-righteous and rigid in their morality, the perfectionist can feel an imagined sense of power, order and safety in their life. They avoid failure at all costs, and never take risks. Much like codependency, this protector can overlap with the others. Paired with the avoidant, the perfectionist morphs into a tyrannical parent-like figure who can overpower and dominate their anxious partner.

The perfectionist ensures not only order, but also the moral high ground, as being perfect makes them divine, and being the ‘rule-setter’ makes them the de facto ‘ruler’. Through constantly telling others what to do, how to behave and what is right, the perfectionist firmly plants themselves in a position of power and control.

The chaos behind the face

To successfully hide the narcissist’s dysfunction, the false self must create an air of flawlessness, superiority and power. Lurking behind this perfectly polished persona, however, is an entire cluster of protective personalities and coping mechanisms. Life is full of stress, unpredictability and suffering. As the narcissist faces the harshness of life, they alternate continuously between these protector personalities, hoping to maintain their false self while avoiding exposure.

The false self is the front guard, which interacts with people while the protectors remain on alert. The paranoid stands by while determining the level of external threat. The schizoid numbs pain, filters out reality, and creates desirable fantasies. The histrionic seduces, while the borderline works to cultivate a perfect love with a replacement parent who will regulate their emotions and never leave. The avoidant maintains a safe emotional distance when threatened. The dependent charms and cultivates closeness. The perfectionist ensures order and moral superiority. These protectors safeguard the integrity of the false self, as the core trauma continues to bubble beneath the surface. Meanwhile, the psychopath maintains a watchful eye, always ready to pounce, manipulate, control, lie or punish to ensure justice and integrity.

Yet while the narcissist has many allies to call on, they cannot control the world. They only have so much power. Often a narcissist grows up in an environment which offers little reinforcement for their imagined superior self. Sometimes catastrophe strikes, and the narcissist is either abandoned, exposed or betrayed to the point of collapse. In such cases, a reorganising of the entire personality is required to ensure survival.

Hiding in plain sight

Like the smooth, glimmering surface of the ocean on a calm, sunny day, the false self hides various lurking predators. These personalities can rise to the surface, then disappear just as quickly. They can remain active for long periods, or dormant ‘underwater’.

For example, when the histrionic actively tries to seduce or gain attention, they are in their overt state. If they are abandoned by their object of desire, then the overt personality falls apart due to histrionic injury. The histrionic may double down and lash out, or withdraw completely, especially if they are broken up with. Over time, the histrionic goes ‘underground’ into their covert, schizoid state and avoids sex and people in general. They remain this way for a time, waiting to restore their confidence and find an opening to reassert themselves as desirable.

The overt and covert states are well-known for narcissists. ‘Classic’ narcissists are easy to spot. ‘Covert’ narcissists are notoriously difficult to identify by those not intimately close to them. Yet all of the protector personalities have both a covert and overt state.

If the narcissist can gain steady supply without opposition, then they will remain in their overt state. Celebrities, politicians, narcissistic parents, company managers, cult leaders and dominant friends all flex their narcissism as far as they can. If a narcissist finds themselves low in a hierarchy, where their need for superiority and grandiosity is constantly challenged or ignored, then they may enter into their covert state to avoid repeated injury.

The environment shapes the narcissist, and their life situation determines how long they remain in their overt or covert state. A narcissist can be abrasive and dominant with their children, yet switch to becoming appeasing and cooperative in the workplace when faced with a powerful, narcissistic boss. That is, they are overt in one environment, and covert in the other.

The covert narcissist can also be difficult to spot at the beginning of the relationship. It is easy to dismiss someone who is acting too abrasive or stuck up. Yet a covert narcissist is typically polite, friendly and deeply interested in you when you first meet. They remain in their covert state until they sense your attachment growing, wherein they gradually switch to their overt state as the balance of power shifts in their favour.

Covert narcissists also behave altruistically, since those who are seen as ‘immoral’ are typically shunned. It is for this reason that narcissists, through their histrionic, sometimes gravitate toward social justice causes, as it forces people to view the narcissist as being on the ‘good’ side while placing the narcissist at the centre of attention.

A house of cards

The false self, above all, aims to protect from pain. This solution is deeply flawed, as the more narcissistic a person becomes, the more they must deny reality. The more reality challenges the narcissist, the more they must double down on their grandiosity. They recruit more people for narcissistic supply, manipulate further, and work harder to reinforce their false self. Eventually, the house collapses, and the narcissist switches to their covert state. The narcissist withdraws from reality to soothe the pain of their disillusionment, while dreaming of a future where they can assert their grandiosity and rebuild their house of cards.

Sometimes the narcissist’s false self is challenged or exposed in a way their ego is ill-equipped to cope with. The calm, confident, seductive exterior collapses, and the narcissist comes face-to-face with their trauma. In such an instance, they revert to the borderline state and become inundated by shame, terror and rage. They act out, attack and lash out in unpredictable ways. They sob, beg, and guilt the other person, using all of the tools at the borderline’s disposal. If damage control is needed, the psychopath may activate, and the narcissist will lie, manipulate or even become violent to punish the other person and restore their dignity and dominance.

This cycle plays out repeatedly, as the narcissist’s house of cards withers to the point of permanent collapse. There is no perfect love to save them, and their desirability reduces as they age and people abandon them one-by-one. At this point in life, a narcissist typically withdraws from society and regresses to the cluster A level. Moving from narcissist, to histrionic, to borderline, through to schizoid and paranoid, they approach their core wound. There is no more pretending. The narcissist becomes cynical, passive-aggressive and bitter, embracing conspiracy as worldview and reality.

The young narcissist looks down the barrel of this downward spiral and senses that they are running on borrowed time. They know that they must avoid this fate at all costs. They have no other choice — they must obtain narcissistic supply, or ‘die’. What they fear is ego death, but this may as well be the real thing. While at the height of their ‘power’, the narcissist therefore employs an instinctive strategy to obtain and hold onto narcissistic supply as long as they possibly can.