Table Of Contents

In Greek Mythology, ‘Narcissus’ was a man of exceptional beauty and arrogance, who spurned all admirers, before falling in love with his reflection in a lake, and seeking to embrace ‘himself’, fell in and drowned.

There are numerous versions of this story, with Ovid’s ‘Narcissus and Echo’ being the most popular. Ovid described Echo, a nymph who was unable to speak, except to repeat the last words spoken by someone else. One day, Echo spotted Narcissus hunting and fell in love with him. Eventually, Narcissus grew frustrated with Echo’s constant repeating of his words, and told her to get lost, in what was perhaps the first recorded description of a narcissistic discard. This left Echo heartbroken and withered.

The myth of Narcissus has particular relevance to today’s discourse on narcissism. For one, we see somebody who accepts admiration from others, yet never their love. This captures the narcissist’s sado-masochistic approach to relationships, sabotaging themselves and others at every turn, proving to be a hard lesson for all who love the narcissist.

Echo, for her part, represents the codependent who admires the narcissist in the wilderness, the latter of which uses their false self to ‘hunt after’ narcissistic supply. Echo mirrors the narcissist’s grandiosity back to them, hoping to be loved and accepted by the narcissist in turn. Many ‘Echoes’ are left hurt, traumatised and ‘withered’ after their ordeal with a narcissist.

Now that narcissists have taken over our public discourse, the tale of Narcissus is not only relevant, it is evolving. Like the Olympian Zeus, the narcissist is now not only considered arrogant, but seemingly all-powerful and all-cunning. Ask anyone online, and they will declare the narcissist to be the destroyer of worlds, the harbinger of suffering, and the villain of dreams.

There is nothing the narcissist can’t do, no limit to their evil ways. Much like the intrigue we find throughout Greek mythology, Narcissus has outgrown his humble beginnings through his manipulation, deception and abusive nature, coming of age as Zeus’ direct challenger. And with that, has also revived the fascination for Greek tragedy in the form of modern psychology.

The Evolution Of Narcissus

While the original Narcissus myth captures a narcissist’s core rather well, our emerging, 21st-century ‘myths’ about narcissists are filling in the gaps.

In the last few decades, the seed of the Narcissus myth from history has blossomed, while modern tales about him have coalesced to rival even Ovid’s ‘Narcissus and Echo’. Narcissus no longer simply spurns lovers; he love bombs them first, before cruelly devaluing and discarding them. Narcissus’ reflection not only deceives Narcissus himself, it also fools others through gaslighting and projective identification. Narcissus now triangulates current and past lovers to incite jealousy, weaves an elaborate fantasy world tailor-made for his ‘Echo’, and tortures and shames Echo in a multitude of ways.

Even Echo is receiving a makeover today. No longer does she wither away and die, having lost her sense of Self and authentic voice. The Echo of this new version of the myth responds by undergoing a heroic journey of self-discovery as she recovers from the abuse. She withdraws her love and emotions from Narcissus to starve him of his supply. She goes no contact where necessary, and seeks to come into contact with her authentic voice within. Courage and truth set Echo free from her tragic fate, and elevate her to exalted status in Mount Olympus.

Alas, a happy ending does not come so easily, however. No matter what we seem to do, narcissists are persistent beings. They shapeshift, able to bypass our awareness and wit. Perhaps the next phase of this evolving myth will reveal Narcissus not as a singular, evil entity, but a multi-headed dragon, or a glimmering, always-changing kaleidoscope we need to remain on the lookout for.

The Elusive Narcissist

‘Proteus’ is a sea god in Greek Mythology, also referred to as the god of ‘elusive sea change’, who could change into any form. Proteus knew everything, including the future, yet shared his gift with nobody — unless they captured him first. To evade those looking to apprehend him, Proteus would assume any necessary shape, such as a lion, a tree or a serpent. Once trapped, however, Proteus would change back to his real form and tell all to his captor.

The narcissist we know is an addict, playing out a predictable script to secure narcissistic supply. Yet the narcissist is also a shapeshifter, much like Proteus. To fool his target, a narcissist takes on whatever form captures the target’s imagination and therefore disarms them. All-wise sage, charming lover, genius, sex siren, authority figure — the narcissist can be anything. As long as the narcissist can maintain the illusion, they evade being exposed. Yet if you corner the narcissist and challenge their grandiosity, the truth of who they are comes out, and you witness their real form — that of a petulant child full of rage and prolonged grief.

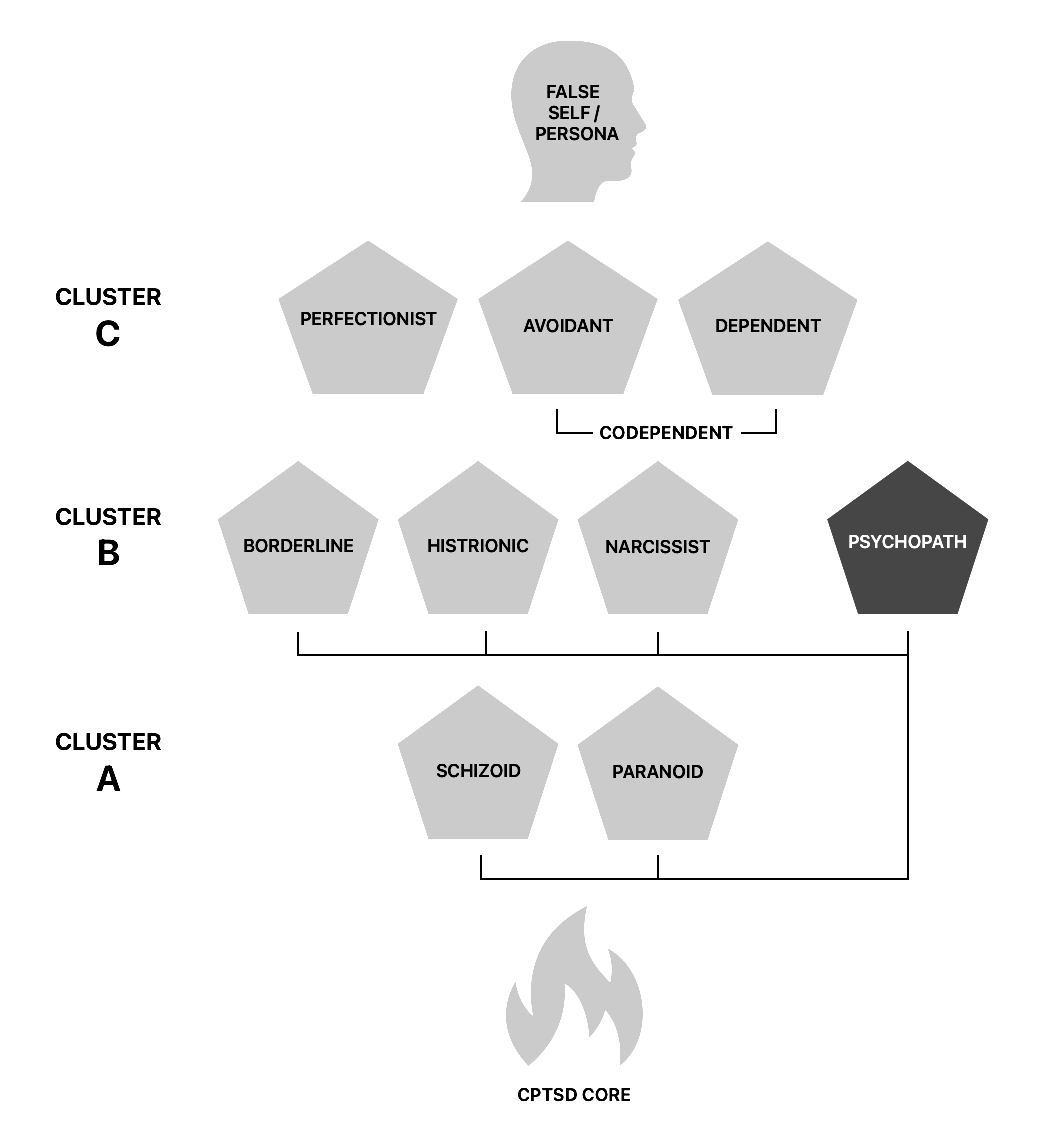

Yet the narcissist’s shapeshifting is driven by more than their false persona. It runs deep into their core trauma and resulting personality structure. We now know that a ‘malignant’ narcissist takes on a psychopathic form, consciously scheming and manipulating in sadistic ways. A narcissist can be ‘covert’, their arrogance and grandiosity hidden behind a mask of niceness or selflessness. A ‘schizoid’ narcissist often spends extended time alone, only occasionally seeking narcissistic supply. Borderlines with a narcissistic exterior are sheep in wolf’s clothing, appearing to be narcissists yet lacking the core features of one. Then there is the histrionic narcissist, obsessed with their appearance and creating drama to draw attention.

The Cluster A, B and C Personality Disorder Map

Yet rather than taking us away from the myth of Narcissus, these developments arising through the Cluster A, B and C map of personality disorders take us full circle, revealing a cosmology of characters resembling Greek mythology as a whole.

Entering The Realm Of The Gods

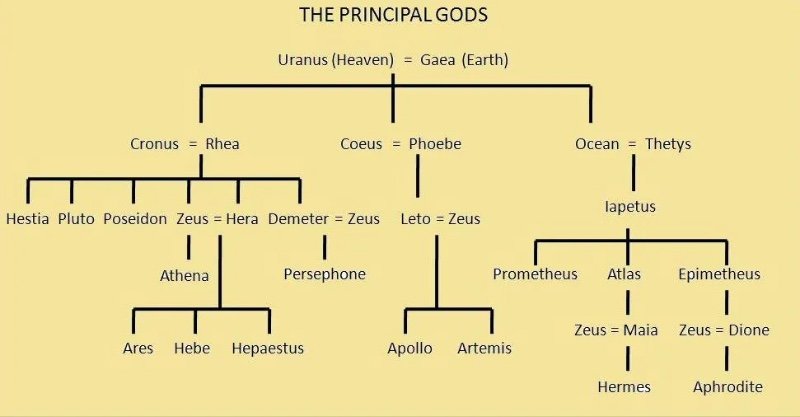

First, it’s important to remember that the Greek Pantheon is effectively a family, consisting of twelve major deities. This family resided on Mount Olympus, giving them ‘exalted’ status.

The ‘Twelve Olympians’, as they are known, included Zeus, Poseidon, Hera, Demeter, Aphrodite, Athena, Artemis, Apollo, Ares, Hephaestus, Hermes, and either Hestia or Dionysus. Each of these figures possessed particular gifts and strengths, but also dysfunctions and weaknesses. What makes the Greek Pantheon so infinitely fascinating is how these various personalities were ‘fated’ to clash based on their strengths and dysfunctional natures.

It’s easy to dismiss the Greek Pantheon as fanciful storytelling, until you consider the view of a child looking up to their family. Are the child’s parents, siblings, uncles, aunts and cousins not incredibly powerful and consequential in the child’s mind? Is this ‘Pantheon’ of our childhood not a manifestation of our imagination, where we see our family members as ‘gods’ with remarkable gifts and strengths?

As we grow older, this magical thinking begins to fade, of course, and we see our family members more clearly in their humanity. But until then, we might as well be interacting with Greek gods. When our father grew angry, it probably felt like he was blasting lightning from the sky like Zeus. When our mother felt crossed by our father or us, her vengeance might have felt like Hera’s spiteful acts towards god and hero alike. Much of Hera’s behaviours represent the corrupted matriarchy of the narcissistic mother, who poisons everyone with her wicked ways.

The sibling structure of the Pantheon is also evocative of the narcissistic family. Zeus is of course the ‘golden child’ of Cronus and Rhea, while Hades the ‘scapegoat’ was cast off Mount Olympus and left to dwell in the underworld. Poseidon, being the god of the sea, is therefore the ‘lost child’ of the family, left to daydream in the vast waters of his unconscious imagination, of which the sea is a symbol.

The seductive and beautiful Aphrodite, reminiscent of the borderline, is another fascinating exception like Hades. She has no father, being born of Uranus’ blood after he was castrated and his genitals tossed into the sea. Borderlines often have a fraught relationship with their absent or emasculated fathers.

The fantastical nature of the Greek Pantheon also harkens back to our childhood via its rootedness in the Greek creation myth. From ‘Chaos’ came Gaia and Uranus, who represent figures of far-off great-grandparents.

During this formative phase of Greek Mythology, you also find a father who imprisons his children, fearing them challenging his power, as we see with first Uranus, and then Cronos. In both cases, a major war between father and son ensued, with the father both times defeated, leading to Zeus’ reign over Mount Olympus. Zeus’ power was so absolute, his very mood dictated the weather, as is the case with an authoritarian parent. Therein we find the universal struggle of all people in dysfunctional families, psychologically imprisoned by a tyrannical parent while ‘battling’ to separate and individuate as a self-actualised adult.

When we grow older and leave the Pantheon behind, we enter into the ‘human’ world. That is, we become mortal. Yet we continue to interact with Mount Olympus, as the dysfunctions of our family continue to act through us via our trauma. The more mental illness in a family, the more its members maintain a foothold in fantasy as a coping mechanism. Those with personality disorders could be considered ‘gods’, while others may be ‘demi-gods’, maintaining a foot in reality and fantasy at the same time.

A Pantheon Of Pathology

The Greek gods represent the best and worst of us. They are the ideal archetypes of what our potential holds, as well as the not-so-ideal archetypes of the worst of our capacities. When we interact with each other via fantasy, that is, when we interact through the Pantheon, people have powers over us which would not be possible were we rooted in reality. When dissociated in fantasy, and when we relate to each other through that fantasy, we can be amazed, charmed and wowed beyond comprehension, yet also psychologically crushed and destroyed to the point of madness.

The closer we look at Greek stories, the more we find that none of this is new. The repeating tragedy of the modern-day ‘personality disordered’ person with childhood trauma echoes much of Greek mythology. All we need to do is widen our lens beyond the original Narcissus myth, and we discover a drama that has been replaying over and over in the same forms between humans.

Codependency creates a constant tension between avoidants, anxiously attached and fearful avoidants. Perfectionism as a trauma response leads to unattainable expectations, harsh judgements and the rampant shame of ‘not being good enough’. Trauma also leads to hyper-vigilance and paranoia, leading to extreme jealousy in relationships, controlling behaviours and even violence.

Psychopaths plot to gain money, sex and dominance. Narcissists are known to lie, cheat and crush the spirit of their targets, sucking the life out of them. Borderlines and histrionics are seductive, playful figures, inspiring attraction, jealousy and acts of madness and betrayal. Do we not see such drama in Greek Mythology?

And yet, such stories, captivating and reassuring as they can be, merely represent human wonder and dysfunction. What truly inspires our fascination is not only the what, but also the why. Why does such madness affect the human condition, and what can we do about it?

Our Newfound Obsession With Tragedy

What made the Greek tragedies so compelling was not only the way they explored human suffering, but also how they attempted to explain the reason behind the suffering.

It might seem like misfortune is rooted firmly in events. Things happen, we suffer. And yet, we humans have gradually come to discover a reality beneath the level of worldly happenings. Through self-investigation, observation and storytelling, we have come to discover forces beyond our control which seem to be following some mysterious design; phenomena which take place in the metaphysical realm beyond our world.

This applies especially to our relationships. On first inspection, it might seem like dysfunction occurs due to bad decisions and selfishness. This is usually the mindset of narcissistic families, who scapegoat certain family members and lay the blame on their ‘immorality’ or ‘stupidity’.

Greek tragedy looked to capture the truth behind our misfortune by calling on the gods to assist. Yet the meaning and symbolism of these characters seem to have been lost.

Alas, the truth never rests.

We now seek to rewrite our foundational mythology through a modern-day exploration of personality disorders. Gradually we are coming to expose personality-disordered people as manipulators of the imagination, luring the ‘mortals’ into their divine game. Whoever dares to believe the psychopath’s deceptions, or fall for the narcissist’s charm, or allow themselves to be seduced by the borderline’s beauty or the histrionic’s sexuality, is doomed to suffer the same fate as those characters in Greek mythology and tragedy.

Yet fate remains fate. No matter what you do, you are always bound to it — to a point.

Being born into a lower-class family or one which carries intergenerational trauma inevitably handicaps us. This is the essence of tragedy. However, humans are not known to accept their fate lying down. By defying the gods, and daring to undertake the heroic journey through the wilderness of our misfortune and trauma, we aim to redeem ourselves by conquering the demons within, emerging into a brighter future — much like the Greek heroes of old.

This is why, despite pagan worship being violently crushed by adherents of monotheistic faiths such as Islam and Christianity, we continue to be dazzled by the old gods, reinventing them to fit our modern day, looking to them to help us make sense of the madness which rules our life.

The Advent Of Neo-Paganism

The revival of tragedy through psychology allows us to make sense of why things happen in ways monotheism cannot.

Pagan gods first emerged as an archaic form of making sense of human behaviour and psychology. Yet as their complexity grew, humans lost themselves in the ensuing drama, ultimately ending up more confused than they began.

Monotheism was the great reset, the hammer which crushed the Pantheon, sending Mount Olympus tumbling in pieces into the sea. From this destruction emerged the ultimate spiritual clarity; a deep and abiding connection to the One God — the source of all things.

Then, when human civilisation reaches its greatest height, pagan worship metastasises with it, reaching a fever pitch. We see this now in the celebrity worship which has gripped the West. The countless gossip magazines aim to re-create the allure of the old gods, yet without the substance of their deeper meaning. Celebrity culture provides empty calories for the soul, and stirs up more emptiness and despair than anything. The reason we are enamoured by celebrities is because they appear like the gods and goddesses of old, as they emulate their posture, behaviour and attire. Nowhere is this more evident than at the Met Gala in Manhattan.

As has been the case throughout human history, decadence corrupts every empire, before collapsing in on itself. War often follows, as the ‘Titans’ or ‘Olympians’ battle for supremacy within the ensuing Chaos, revealing once again the reality of the One, True God. Once a new civilisation or ‘order’ is established, the drama repeats yet again, as humans scramble for power in their families, communities and between nations, which resembles the intrigue of Mount Olympus.

This cycle repeats over and over, as the inevitable collapse comes once again due to a concentration of power and human hubris, heralding in yet another round in the constant tension between pagan complexity and monotheistic simplicity, in our endless search for ultimate truth.