The narcissist conditions their target to admit weakness. They will pounce on an admission of inferiority, or a stutter, or you waking up late compared to them. On the other hand, when the target brags or achieves something great, the narcissist puts it down. As the target then feels shame and admits weakness, the narcissist grows amused and reinforces it.

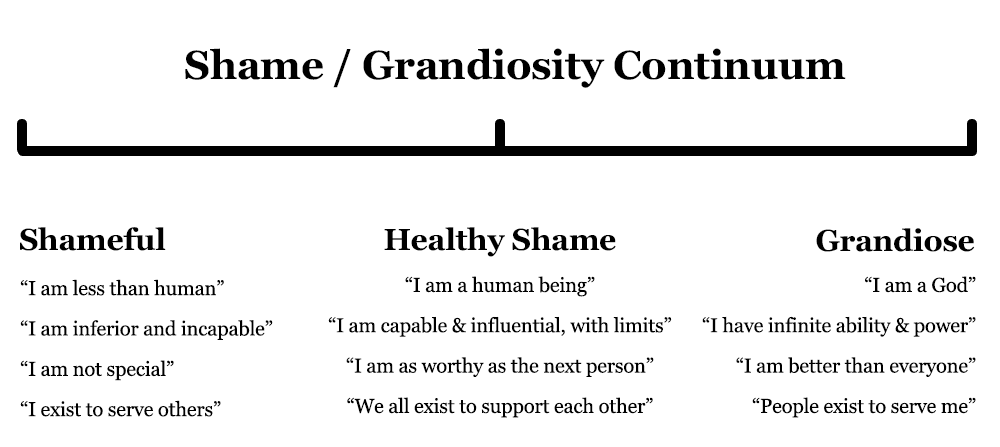

This is how the narcissist manipulates the shame/grandiosity continuum, which is a paradigm; a set of psychological glasses that affect how we see the world.

When we meet someone, they may exhibit a set of behaviours that create the impression of high status, such as posture, attire, career, emotional restraint or how they treat us. Somebody else may tell us that this person is famous or talented at something. As a result, we might designate that person as being ‘better’ than us. This is commonly referred to as the ‘halo effect’.

If someone self-deprecates before us or is clearly lacking in confidence, we might start seeing ourselves as ‘better’ than them. This is a standard ego function, used to help the mind determine who is of higher status, and therefore helps us determine how they might be useful or harmful to our survival or reputation.

A narcissist places exaggerated importance on this scale. They categorise every person they meet based on two criteria:

1. Are they higher or lower status?

2. Is there anything they can offer me?

The narcissist’s treatment of others depends entirely on how they perceive the person, based on a combination of the above criteria:

- Lower status, offers something: The narcissist will work to keep that person as low on the continuum as possible while drawing narcissistic supply from them. When a person of lower status cuts off supply by disengaging, the narcissist will use rage, charm, a wall of silence, guilt or shame to re-engage the target.

- Lower status, offers nothing: This is a no-brainer. The narcissist will ignore or discard that person immediately. A person of perceived lower status can move between being useful and not useful, especially when they are an acquaintance, although significant partners are not immune to being discarded either.

- Higher status, offers something: This can be useful. The narcissist may try to push that person down the scale by shaming them, but if the person has strong boundaries and cannot be manipulated, the narcissist will appease and charm that person with the hope of gaining status, attention or resources. This is commonly seen in companies, where a malicious, manipulative, narcissistic boss becomes suddenly placid and cooperative in the face of a CEO of higher status in the company.

- Higher status, offers nothing: This is the worst possible case. The narcissist will envy and despise that person from a distance.

Anybody who unconsciously adopts this paradigm in their life is susceptible to being a victim of narcissism, or capable of inflicting narcissistic abuse — narcissists included. This ‘better than’ / ‘less than’ scale is an unconscious ego trap which we can all fall into.

By viewing somebody as having higher status and believing they can offer us something, we get sucked in and become susceptible to that person’s whims. If we meet somebody who we perceive as having lower status, we may unconsciously play out how we’ve seen other narcissists behave by shamelessly putting down that person or trying to control them, just to get an ego boost.

Seeing others as only higher or lower status is a recipe for disaster. We cannot turn off our ego functions, but we can control how we act. We must never sacrifice our sense of dignity in service of a person of perceived higher status. It is equally important that we do not shame others who find themselves further down the scale than us.

In any relationship, the key is shared shame; to find intersecting ways to dwell on the same position of the shame/grandiosity continuum. That way we can connect with others based on shared experience and mutual growth, which is far more meaningful and satisfying than the narcissist’s way of doing things.